By Mike Swiger

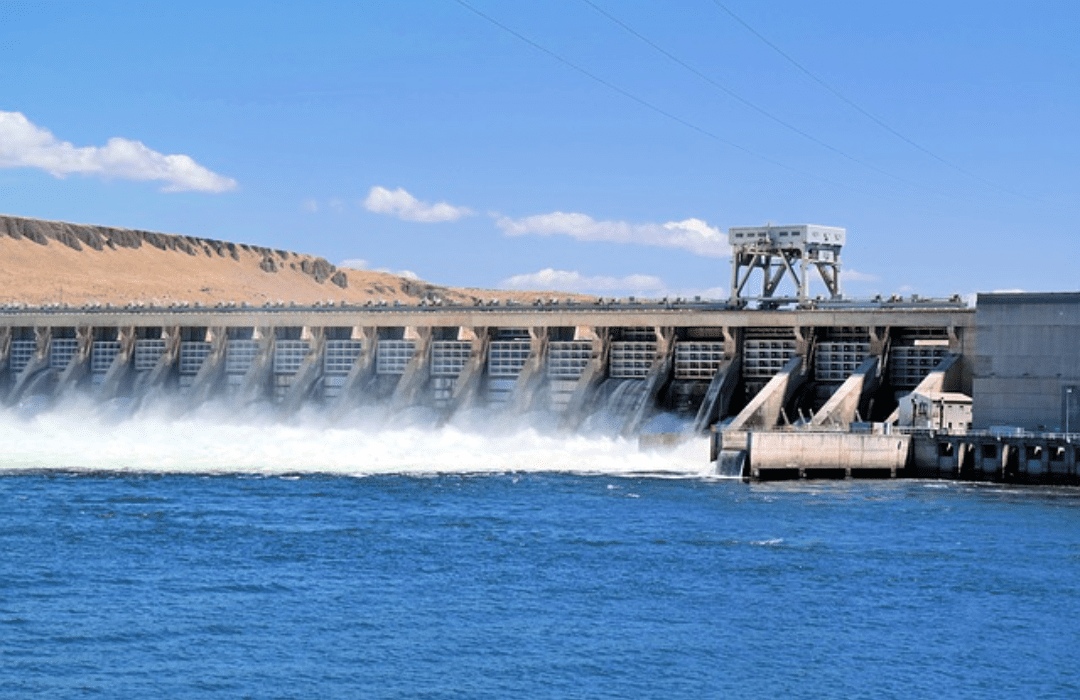

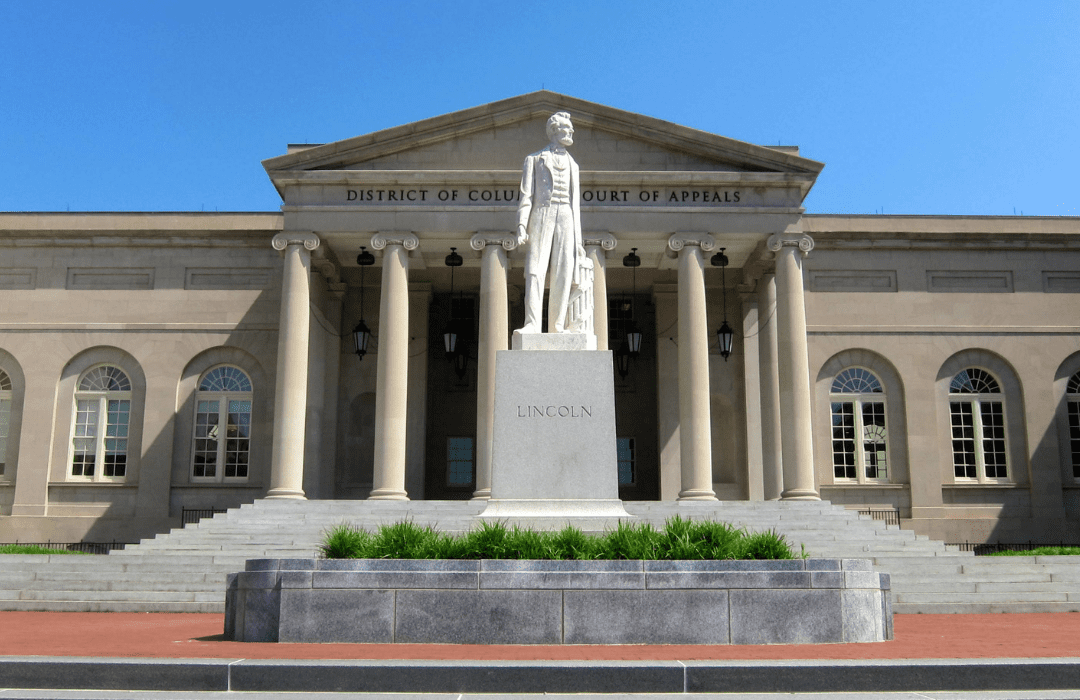

Two recent U.S. Court of Appeals decisions involving water quality certification under Section 401 of the Clean Water Act (CWA) would put state water quality agencies in charge of setting the timelines for federal licensing and permitting actions. This is in spite of Section 401’s express one-year limitation for state agencies to act on a certification request.

A June 2022 decision by a three judge-panel of the D.C. Circuit in Turlock Irrigation District, et al. v. FERC upheld the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (FERC) interpretation of Section 401; specifically, the panel agreed with FERC that when a state repeatedly denies certification “without prejudice” year after year, it has not failed or refused “to act” within the meaning of the statute. Consequently, the state has not waived its authority to issue a certification in response to a later request.

In a second decision, which was issued on August 4, 2022, a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit in SWRCB, et al. v. FERC overruled FERC in holding that when the state cooperates with an applicant in repeatedly withdrawing its certification request just prior to the one-year deadline and then re-filing the application to trigger a new one-year deadline, then the state is simply accommodating the wishes of the applicant and not attempting to evade the deadline – therefore a waiver does not occur.

If the two decisions stand, they threaten to perpetuate a situation in California and other states in which the Section 401 certification process has delayed FERC hydroelectric license proceedings for years, and sometimes decades. Developers of new projects may be subjected to continued uncertainties, costs, and delays due to the states’ control over when FERC can issue a license. Licensees of existing projects seeking relicensing would also suffer from uncertainty as the FERC process is held up for years, often with no end in sight.

SETTING THE STAGE

Under CWA Section 401, if an applicant for a federal license or permit conducts an activity that may result in a discharge into waters of the United States, the applicant must request a water quality certification from the state, or states, in which the discharge will originate. This certification provides the state with the opportunity to review the project and impose conditions necessary to ensure it will comply with state water quality standards. If the state deems the project will not comply with the water quality standards, the state may choose to veto the federal license or permit.

If the state “fails or refuses to act” on a certification request within a reasonable period of time, which shall not exceed one year, then the state waives its certification authority. The courts have explained that the purpose of the waiver provision is to prevent a state from indefinitely delaying a federally licensed project by failing to issue a timely certification. However, states have invented various procedural mechanisms over the years to avoid the one-year timeline, as FERC has complained on a number of occasions to Congress.

The D.C. Circuit offered hope for FERC’s ability to reassert control of its licensing timelines from Section 401 delays when it decided Hoopa Valley Tribe v. FERC in 2019. In that case, the court determined that a written agreement between an applicant for water quality certification and the states of California and Oregon, by which the applicant annually withdrew and re-filed the same request while the parties pursued a dam removal settlement, constituted a “waiver of authority” by the states.

Spurred by Hoopa Valley Tribe, FERC found waiver in a number of cases in California. These cases were based on California’s entrenched practice, not limited to Hoopa Valley Tribe, of encouraging hydroelectric applicants to withdraw their certification requests just prior to expiration of the one-year deadline. The state would then encourage applicants to re-file identical requests to initiate a new one-year period for review. FERC had been prevented from issuing new licenses in these cases for years, and in some cases decades, while the state orchestrated the annual ritual of withdraw-and-re-file.

FERC’s waiver determinations appeared to uncork the bottleneck by giving FERC legal authority to move forward with its license decisions in the delayed proceedings without state water quality certifications. FERC did promise to consider the state’s recommendations in imposing its own conditions on the licenses.

Meanwhile, California began issuing denials of certification “without prejudice” to the applicant re-filing its certification request to kick off a new one-year review period.

THE COURT OF APPEALS DECISIONS

The California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) challenged three of FERC’s post-Hoopa Valley Tribe waiver decisions in the Ninth Circuit. The cases were consolidated because they presented similar fact patterns and essentially the same legal issues. FERC and the three licensees and member organizations of the National Hydropower Association (NHA) – Merced Irrigation District, Nevada Irrigation District, and Yuba County Water Agency – argued that the SWRCB coordinated the withdraw-and-re-file scheme and therefore intentionally sought to evade the one-year deadline as it had for decades in numerous other cases in California.

Emails between SWRCB staff and the licensees corroborated this argument. The court, however, agreed with the SWRCB that the licensees voluntarily withdrew and re-filed their certification requests for their own purposes, and that the SWRCB was justified in not acting on the requests because state law required completion of a state-level environmental review, which had not yet commenced.

The court ignored evidence that the state-level review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) could not be completed within the CWA 401 one-year timeframe and thus was fundamentally incompatible with the federal statute.

In Turlock, the D.C. Circuit (a different panel of judges than in Hoopa Valley Tribe) blessed the SWRCB’s now-favored practice of denial “without prejudice.” The co-licensees, Turlock and Modesto irrigation districts, twice filed certification requests with the state, and each time the state issued a denial without prejudice to re-filing the application. The state’s denials were based on the fact that FERC had not yet completed its National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) document, and the districts, as lead agencies, had not completed CEQA review.

The districts filed a third request, but then withdrew it upon filing a petition for declaratory order with FERC, asserting that the state had waived certification through repeated, rote denials without ruling on the substance of their request. FERC denied the districts’ petition, holding that a denial, even “without prejudice,” is still a denial and thus an “act” within the meaning of Section 401.

On appeal to the D.C. Circuit, the districts argued that if FERC’s ruling were upheld, states could extend the time for decision indefinitely by denying one certification request after another without prejudice, thereby nullifying Section 401’s one-year limit. The court, however, agreed with FERC’s interpretation of the statute and dismissed the districts’ argument as a “slippery slope” hypothetical.

WHAT COMES NEXT?

The waters continue to roil on the CWA Section 401 timeline issue. Turlock and Modesto irrigation districts recently filed for a rehearing en banc before the full D.C. Circuit, pointing out that their case cannot be reconciled with Hoopa Valley Tribe.

The Ninth Circuit decision could be appealed as well.

The Second and Fourth Circuits also have recently weighed in on FERC waiver determinations.

Meanwhile, Congress has taken a strong interest in the Section 401 timeline issue and may take it up as part of a permitting reform package in the fall of 2022.

The landscape may not be settled for some time, so hydropower licensees and project developers should stay tuned as FERC and the courts attempt to reconcile and resolve the various cases.

Originally appeared in the National Hydropower Association's Powerhouse Newsletter.